|

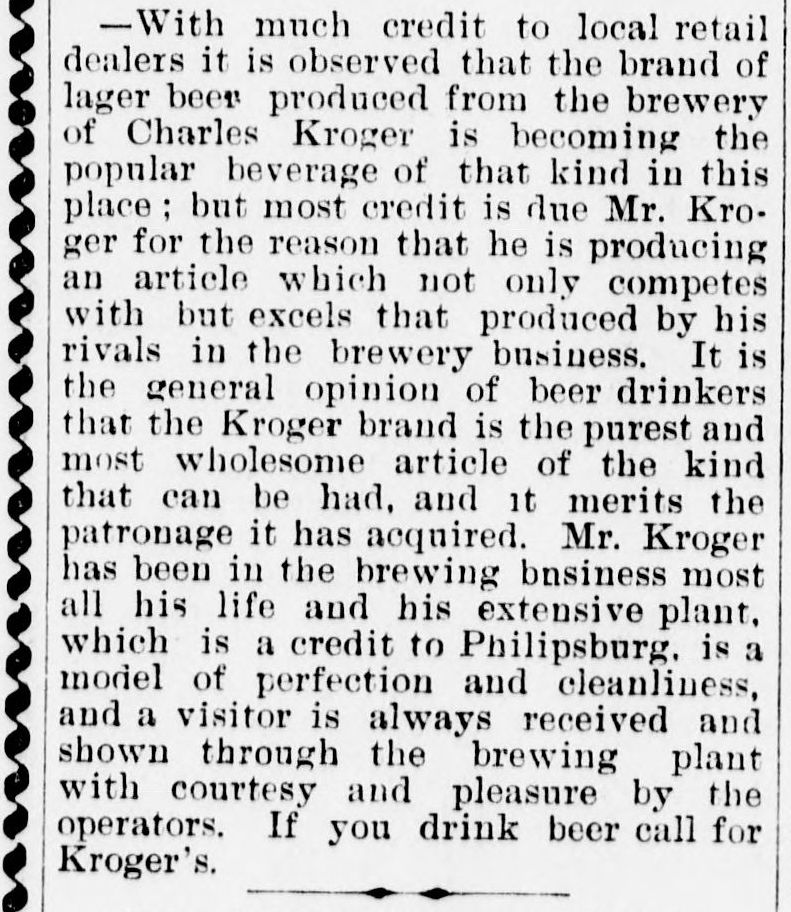

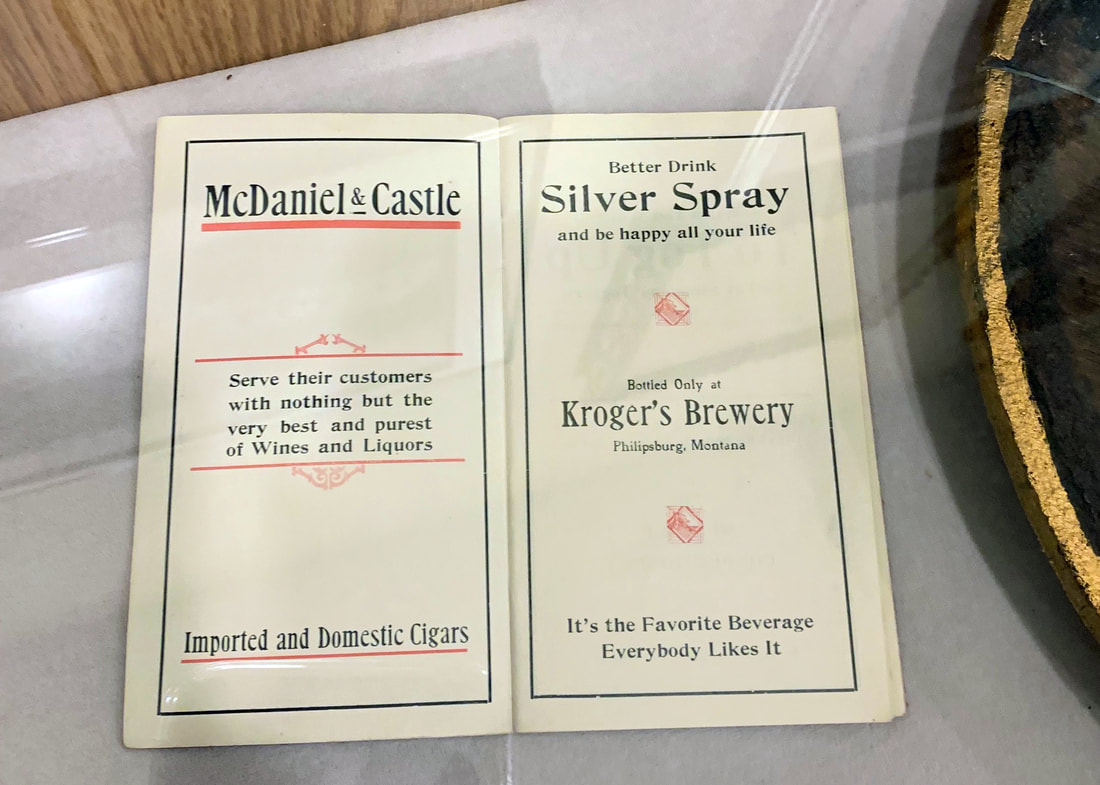

A keg saved my life today. If you found yourself in Philipsburg, Montana on a particular June day in 1876, you might have heard those words upon an encounter with Mr. Charles Kroger, the celebrated owner of the town’s first brewery (at the same site on which we brew today: the Springs). Mr. Kroger’s brush with death occurred while on the clock, heading home from delivering beer, “that modern essential to comfort,” as the local paper described it in those days (seems not much has changed). As reported in the Helena Weekly Herald’s “Territorial News” section, “C. Kroger, returning from Bear to Philippsburg with an empty beer wagon, came near losing his life while crossing Flint creek. … He lost his team, and barely succeeded in navigating to the shore on an empty beer keg.” Charles Kroger was a bit of a celebrity in Philipsburg (sometimes spelled with two P's at that time); regional newspapers gushed about his business from the day he purchased the land. In 1876 Kroger’s Philipsburg brewery had only been open a year, but the town was growing, attracting more hard-drinking miners without family obligations to keep them in check (women and children were a very rare sight). The “Bear” that the Herald reports Kroger coming from was likely Beartown, the mining camp that he moved to Philipsburg from. Beartown formed in 1865 when gold was struck on Bear Creek, about six miles from the Bearmouth area (by a group clearly lacking in creativity, at least when it came to naming). Beartown was known as “a rowdy, lawless camp that drew prospectors from far and wide” and Kroger likely contributed by running his first brewery there. He shared a house with two other men, one of which was also a brewer. Kroger gained at least five years of brewing experience, while also mining, before meeting his wife and opening the Philipsburg brewery. We like to imagine that Kroger’s wife, Anna, was a beer lover too, encouraging his entrepreneurial spirit. Although they met in Deer Lodge, both Anna and Charles were from Germany after all, where beer is a major part of the culture. It’s understood that the large number of immigrants from strong beer-drinking countries (like Germany) directly contributed to the emergence of America’s beer culture. Incredibly, per capita consumption rose from under four gallons in 1865 to 21 gallons in 1910! Kroger’s Brewery sold beer in both bottles and kegs, and, like most breweries of the time, delivered customer orders on a horse-drawn beer wagon. Kroger was driving his wagon with a lightened load after (presumably) delivering beer to Beartown. And then he lost his horses and almost died in Flint Creek. So few details, so many questions! First of all, we’re told Kroger needed to grasp an empty beer keg to “navigat[e] to the shore” of… Flint Creek?! Locals know Flint Creek as quite narrow, shallow, and slow-moving; it’s tough to imagine it drowning a man. Which tells us Kroger must have been seriously injured if he struggled to get to shore. How might this have happened? Brewery horses had to be well-trained, but like any horse, they could spook and bolt, breaking free of the wagon or bringing it for the ride, ramming people and buildings and throwing contents to the ground. Drivers themselves were thrown as well (or they chose to jump off), causing head injuries and broken legs, ribs, and necks, sometimes even death. This was actually quite a common sight in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; newspapers were full of stories of “runaways” and their aftermath.

Now consider that Kroger was not in town, but, instead, alone in the country. Those of you lucky enough to have spent the nineties playing Oregon Trail, think back to those tricky river crossings in which any number of things could go wrong, like the wagon getting stuck in the mud or breaking a wheel—and that was with oxen, which were better behaved than horses. Then consider that many horses have a fear of water, even as small as a puddle. We’ll let you do the math from here, but whatever happened that left Kroger in Flint Creek and his team of horses running wild, he eventually managed to make it back to town to tell the story and keep the beer flowing in “unlimited” quantities. That wasn’t the last of Kroger beer wagon runaways, but likely the most memorable. We say beer wagon drivers were mining town heroes, risking life and limb to supply “that modern essential” to the people. Kroger and company fulfilled that mission ‘til the end, or what surely felt like the end: prohibition. We’re proud to continue his work today, brewing and bottling on the original site, where Kroger’s hoptower stands to this day.

1 Comment

One need not be a history buff or student of architecture to appreciate the distinct character of the buildings lining Philipsburg, Montana’s business district and surrounding neighborhoods. If you’re lucky enough to have visited our town, one building in particular has surely caught your eye: the colorful, ornate, and towering Sayrs building at the corner of Broadway and Sansome. Yes, the one with BREWERY inscribed in big gold letters on it’s big glass windows. Call us biased, but we have to say our Sayrs home is Broadway’s architectural champion. Constructed by banker Joseph Hyde and his wife, Mary, in 1888, the Sayrs building was originally known as Hyde Block. It housed First National Bank until the silver crash in 1893, then reopened in 1894. The bank inspired the name of our taproom, as the original vault remains, just to the left of the bar. The Sayrs name graced the building in 1904 when Frank Sayrs bought it, and since then it’s housed a variety of businesses––including a tailor’s shop, drug stores, clothing store, liquor store, and recreation center––until 2012, when a gang of craft beer obsessives moved in with tanks, kegs, and a dog named Bruce. Of course, our building is just one of the architecturally interesting structures in town, many of which are on the National Register of Historic Places. Philipsburg grew rapidly from the start, but it was two decades after settlement began that the most significant buildings were constructed––during the silver mining boom between 1881 and 1893, and again, to a lesser extent, during the early 1900s. Most construction even utilized locally sourced materials, including granite, brick, and wood, long before it was a box to check on your LEED application. Philipsburg is now considered one of Montana’s best-preserved late-nineteenth-century mining towns. We’re so proud of our history that we’re just going to say it: you should make the trip to Philipsburg while the weather’s still gorgeous for an afternoon stroll around town––with an eye on design and a beer in hand. Yep, it’s legal to drink in the streets (one more reason to love Philipsburg!), so the Sayrs building is an obvious first stop. Read on for a quick lesson in architectural vocab to impress your friends when you make that trip, and grab a free Philipsburg Territory at any local business for a historic district map and guide (pages 16-24). Spot these architectural elements on Philipsburg's historic buildings:

Think you’ve got it down? Head into town to test your knowledge or just stare at all the pretty. We’ll be waiting with your pint in the Sayrs building, every day from 10:00 to 8:00.

And one last thing! The stories of the people and businesses that occupied these architectural gems are seriously fascinating but far too numerous to include here. So if you’re itching for more, we highly recommend stopping by our local library, which has a section dedicated to books on Philipsburg history and cheerful librarians to help you browse. As our pal Arthur says, “Having fun isn’t hard when you’ve got a library card!” |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed